By David Schoenfield and Thomas Neumann

At the start of the season, the Tampa Bay Rays were 80-1 long shots to win the World Series.

So, if you had bet $100 with your favorite illegal offshore betting Web site legal wagering outlet in the state of Nevada, you would be in line to win $8,000.

Alas, you didn't do that -- which is why the Rays can fairly be referred to as a miracle team. They've become just the third team to reach the World Series after 10 or more consecutive losing seasons. Only one team has advanced to the World Series after losing more games the previous season (the 1990 Atlanta Braves lost 97 games, one more than Tampa Bay lost a year ago). Most importantly, they're the Rays, the franchise best known for employing Jose Canseco, once having a local furniture store put up a display in the Tropicana Field concourse and … umm, getting into that big fight with the Red Sox a few years ago.

But here they are -- a young, talented, good baseball team, playing for a World Series title. They've inspired us to look back at some of sports' other miracle seasons, teams that unexpectedly advanced to the championship of their sport, rated from one to five on the Page 2 miracle scale.

2008 Tampa Bay Rays

2007: When the Devil Rays changed their name after the 2007 season, the snickers were loud and clear: Like that would make a difference? Tampa Bay had played 10 seasons and lost 90-plus games in all of them. They finished 66-96, allowing the most runs in the AL. The bullpen was one of the worst in major league history, going 21-34 with a 6.16 ERA.

2008: A 19-10 May pushed the Rays into first place, but a seven-game losing streak before the All-Star break raised doubts. However, they went 21-7 in August and held off Boston to win the AL East at 97-65. The pitching staff allowed 671 runs, second in the AL, and an incredible 243 fewer than it allowed in '07.

Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

The Tampa Bay Rays are the latest entrant into the miracle teams clique.

Smart moves they made: Many franchises would have fired manager Joe Maddon after losing 101 and 96 games his first two seasons. Tampa set out to improve its defense, one of the worst in the majors in 2007: B.J. Upton was moved to center field full-time; former No. 1 pick Delmon Young was traded for shortstop Jason Bartlett and pitcher Matt Garza; and rookie third baseman Evan Longoria stepped in at the hot corner. Years of losing meant lots of high picks (Upton was the second overall pick, Longoria third), and the Rays had acquired talented arms like Edwin Jackson and J.P. Howell, one-time top prospects who hadn't yet performed at the big league level.

Where they got lucky: The rotation stayed healthy and Jackson and Andy Sonnanstine improved from 2007, but the big breaks came in the 'pen. Howell, with a career ERA over 5.00 in three seasons, became one of the best relievers in the AL, pitching 89 innings with a 2.22 ERA. Grant Balfour, acquired in 2007, had never done much in the majors, but held hitters to a .143 average. Dan Wheeler, also acquired last season, lowered his ERA from 5.30 in '07 to 3.12.

Was it a fluke? Like the other four "miracle" baseball teams on this list, the Rays built around young pitching (at 26, James Shields is the oldest of the team's five starters), and now they have David Price on the way. An offense built around Longoria (22), Upton (23), Carl Crawford (26) and Carlos Pena (30) should be at least solid for several years.

Miracle rating:

2008 Boston Celtics

2006-07: 24-58, last place in Atlantic Division and worst record in Eastern Conference; widely accused of tanking games down the stretch to position themselves to land Greg Oden or Kevin Durant in the 2007 draft.

2007-08: 66-16, first place in Atlantic Division with best record in NBA, won NBA Finals.

Smart moves they made: Acquired Kevin Garnett from Minnesota for Al Jefferson, Ryan Gomes, two first-round draft choices and assorted spare parts. Acquired Ray Allen and Glen Davis from Seattle for Delonte West, Wally Szczerbiak and Jeff Green. Signed role players James Posey and P.J. Brown. Didn't allow Brian Scalabrine to play any meaningful minutes.

Where they got lucky: Former Celtics great Kevin McHale remained employed long enough by the Timberwolves to deliver a championship -- albeit to his former team. … Brown surprisingly providing clutch shooting and rebounding in the waning minutes of Game 7 of the Eastern Conference semis against the Cavaliers.

Was it a fluke? The Celts certainly appear to still be the class of the East as the 2008-09 season begins. It remains to be seen how much the losses of Posey and Brown will affect the team.

Miracle rating:

2006 Detroit Tigers

2005: 71-91, fourth place in AL Central, their 12th consecutive losing season. They weren't particularly young either -- starter Jeremy Bonderman was the only regular position player or pitcher under 25.

2006: 95-67, second place in AL Central, earned wild card, lost World Series. Justin Verlander emerged in a big way, going 17-9 and winning AL Rookie of the Year honors. Bonderman, Nate Robertson and Kenny Rogers also won at least 13 games apiece as the team improved from eighth to first in runs allowed.

Smart moves they made: Acquired Placido Polanco from Phillies for Ugueth Urbina and Ramon Martinez. Promoted Verlander from Double-A. Signed 41-year-old free agent Rogers. Made Curtis Granderson the full-time starter in center field. Converted flamethrowing rookie Joel Zumaya to the bullpen with great results. Named Jim Leyland manager. Shared champagne with the paying customers after ousting the Yankees in the ALDS.

Where they got lucky: Tigers players reacted positively when Leyland pushed and prodded them with his nicotine-stained fingers. The feisty skipper unleashed a legendary tirade after his team fell to 7-6 after a rout at the hands of Cleveland, and the Tigers responded by winning 28 of their next 36. … Chris Shelton did his best Babe Ruth impression, hitting nine homers in the first 13 games of the season. Then he did his best Stan Papi impression, hitting just seven more in his next 102 games. Fernando Rodney had a career year in middle relief.

Was it a fluke? Yes. The ride got bumpy when the Tigers' pitching came back to Earth in 2007 and the team missed the playoffs by six games. Then the chassis fell off in 2008 despite a major boost in payroll and the additions of Miguel Cabrera, Dontrelle Willis and Edgar Renteria.

Miracle rating:

2002-03 Mighty Ducks of Anaheim

2001-02: 29-42-8-3, 69 points, finished last in Pacific Division for third consecutive season.

2002-03: 40-27-9-6, 95 points, second place in Pacific Division with No. 7 seed in Western Conference, lost in Stanley Cup finals.

Smart moves they made: Flipped half the roster from the previous season, notably acquiring Petr Sykora, Rob Niedermayer, Adam Oates and Sandis Ozolinsh. Promoted coach Mike Babcock from the team's top farm club in Cincinnati. Oates, Paul Kariya and Jean-Sebastien Giguere also filmed this wonderfully cheesy commercial.

Where they got lucky: Giguere stood on his head the entire postseason, becoming the fifth player to win the Conn Smythe Trophy despite not winning the Stanley Cup. Giguere posted a playoff shutout streak of 217 minutes, 54 seconds, including three consecutive shutouts against Minnesota to open the Western Conference finals. It was the longest such streak in the NHL since 1951.

Was it a fluke? Yes. Anaheim slipped to fourth in the Pacific the next season. By the time the Ducks reached the playoffs again, in 2006, the roster was largely retooled, and Randy Carlyle had replaced Babcock behind the bench.

Miracle rating:

1999 St. Louis Rams

1998: 4-12, tied for last in the NFC West in their ninth consecutive losing season. The Rams ranked 24th in the NFL in points scored and fewest points allowed, and they ranked 27th in turnover differential at minus-10.

1999: 13-3, NFC West champions and top seed in NFC, Super Bowl XXXIV champs. The Rams scored the most points in the NFL and ranked No. 4 in fewest points allowed. They improved their turnover differential to plus-five, which ranked ninth in the league.

Smart moves they made: The Rams acquired Pro Bowl running back Marshall Faulk from the Colts for a second- and a fifth-round draft choice. They also landed Torry Holt and Dre' Bly in the first two rounds of the draft. Most importantly, they concluded that Tony Banks wasn't, in fact, the team's quarterback of the future.

Where they got lucky: Quarterback Kurt Warner emerged from total unknown to NFL MVP after starter Trent Green suffered a season-ending knee injury during the preseason. It's safe to say the Rams were clueless as to what they had in Warner, since he spent 1998 behind Banks and 36-year-old Steve Bono on the depth chart. In 1999, Warner completed 65.1 percent of his passes with 41 touchdowns, both NFL bests. Faulk also turned in the best season of his career, with 87 catches, 5.5 yards per carry and 2,429 yards from scrimmage.

Was it a fluke? No. St. Louis ushered in the "Greatest Show on Turf" era by leading the NFL in both points and yards gained from 1999 to 2001. After the '99 season, the Rams made the playoffs in four of the next five seasons. They reached Super Bowl XXXVI after the 2001 season, but were memorably upset by 14-point underdog New England.

Miracle rating:

1998 Atlanta Falcons

1997: 7-9, 13th losing season in 15 years.

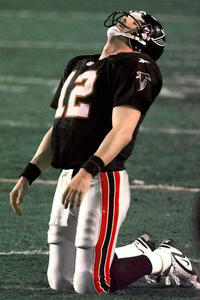

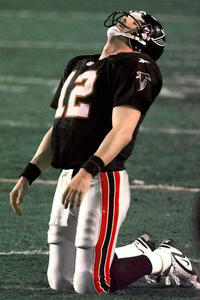

AP Photo/Elise Amendola

The miracle season crashed and burned for Chris Chandler and the Falcons in Super Bowl XXXIII.

1998: 14-2, won NFC West, lost Super Bowl XXXIII. Quarterback Chris Chandler, who ended his career with a passer rating of 79.1 and a 67-85 record as a starter, posted career bests with 3,154 yards, 25 touchdowns and a 100.9 rating. Running back Jamal Anderson also had a career year, rushing for 1,846 yards on 410 carries.

Smart moves they made: Signed safety Eugene Robinson away from the Packers. Drafted offensive tackle Ephraim Salaam (who started all 16 games) in the seventh round and return man Tim Dwight in the fourth round.

Where they got lucky: Minnesota kicker Gary Anderson missed a 38-yard field-goal attempt with 2:07 left in regulation in the NFC Championship Game after going 39-for-39 to that point in the season. That allowed the Falcons to beat the high-octane Vikings on a 38-yard Morten Andersen field goal in overtime. Robinson's high moral character rubbed off on teammates during a triumphant Super Bowl weekend in Miami.

Was it a fluke? Atlanta went 16-32 over the next three seasons. You be the judge.

Miracle rating:

1991 Minnesota Twins

1990: 74-88, last in the AL West. Twins ranked 12th in the AL in runs scored and 10th in runs allowed. They were next-to-last in home runs and only one pitcher won more than eight games.

1991: 95-67, beat the Atlanta Braves in the World Series, becoming the first major league team to go from last place to World Series champs.

Smart moves they made: The Twins took a chance on two veteran free agents, pitcher Jack Morris (a Minnesota native) and designated hitter Chili Davis. Morris, coming off two subpar years with Detroit, went 18-12 with a 3.43 ERA. Davis added much-needed power, hitting 29 home runs and driving in 93 runs. The other big improvements came from second-year starters Kevin Tapani and Scott Erickson, who went 16-9, 2.99 and 20-8, 3.18, respectively. They promoted second baseman Chuck Knoblauch, a No. 1 draft pick in 1989, from Double-A and he was named Rookie of the Year. Replaced third baseman Gary Gaetti (a black hole with his .274 OBP in 1990) with a Mike Pagliarulo/Scott Leius platoon that was at least decent. Essentially, the Twins perfectly identified their weaknesses from 1990 and filled the gaps.

Where they got lucky: Middle reliever Carl Willis, who had a 6.39 ERA in Triple-A in 1990, went 8-3 with a 2.64 ERA in 89 innings. Yes, the Twins probably got more than they could have expected from Morris and Davis, but youngsters Tapani, Erickson and Knoblauch also speared the improvement. The rest of the core -- Kirby Puckett, Kent Hrbek, Shane Mack, Brian Harper, Greg Gagne, Rick Aguilera -- performed about the same as the year before.

Was it a fluke? They were able to sustain their success for only one more year. The Twins lost Morris as a free agent in '92 but traded for John Smiley, who won 16 games, and they finished 90-72. However, after '92 they lost Smiley, Davis and Gagne to free agency, Tapani and Erickson declined, the farm system dried up and the franchise began a long dry spell.

Miracle rating:

1991 Atlanta Braves

1990: After winning the NL West in 1982, the Braves had become baseball's laughingstock by the late '80s, playing in those ugly blue uniforms, registering the worst attendance in the league and finishing with the worst record in the NL from 1988 to 1990, when they went 65-97, ranking last in the NL in runs allowed.

1991: Edged out the Dodgers for the NL West title with an eight-game winning streak in late September, finishing 94-68. Beat Pittsburgh in seven games in the NLCS, lost to Minnesota in seven games in the World Series.

Smart moves they made: The Braves had one clear offseason plan: improve the defense. Terry Pendleton, Sid Bream, Otis Nixon and Rafael Belliard were signed as free agents, all regarded as excellent defensive players. But the foundation had already been set back in 1987, when the team traded Doyle Alexander to Detroit for a minor leaguer named John Smoltz, and Tom Glavine reached the majors. Steve Avery, the team's No. 1 pick in 1988, reached the bigs in 1990. Along with veteran Charlie Leibrandt, the three youngsters (at 25, Glavine was the oldest), helped the Braves move from last to third in run prevention. The offense dumped its two worst players from 1990 (third baseman Jim Presley and washed-up vet Dale Murphy) and improved to second in runs.

Where they got lucky: Pendleton, who had been a league-average hitter just once in his five full seasons with St. Louis, became one of the most improbable MVP winners ever, hitting .319/.363/.517. Juan Berenguer, another free-agent signing, had the best year of his career, with 17 saves and a 2.24 ERA. Platoon second baseman Jeff Treadway hit .320, 39 points above his lifetime average.

Was it a fluke? No. The Braves would go on to win an amazing 14 consecutive division titles, topping 100 wins six times and winning the 1995 World Series.

Miracle rating:

1991 Pittsburgh Penguins

1989-90: 32-40-8 (72 points), finished fifth in Patrick Division, the seventh time in eight seasons the team had finished fifth or sixth in its division.

1990-91: 41-33-6 (88 points), finished first in NHL Patrick Division with No. 3 seed in Wales Conference, won Stanley Cup.

Smart moves they made: Fleeced Hartford by acquiring Ron Francis, Grant Jennings and Ulf Samuelsson from the Whalers for Zarley Zalapski, John Cullen and Jeff Parker. Acquired defenseman Larry Murphy from Minnesota. Hired legendary coach "Badger" Bob Johnson.

Where they got lucky: Mario Lemieux was able to return from back surgery to lead the NHL in playoff scoring with 44 points in 23 games. Mark Recchi emerged with 113 points, fourth in the league, in just his second full season. Eighteen-year-old rookie Jaromir Jagr had yet to discover the permed mullet, but he did debut with 57 points in the regular season and 13 more in the postseason, including a game-winning goal against the Devils in the first round.

Was it a fluke? Hardly. It was the first of 11 consecutive playoff appearances for the Pens. Johnson left the team because of health concerns that summer and died of cancer the following winter. Scotty Bowman took over for Johnson and piloted the team to another title in 1991-92.

Miracle rating:

1981 San Francisco 49ers

1980: 6-10, missed playoffs for eighth consecutive season.

1981: 13-3, NFC West champions, top seed in NFC, Super Bowl XVI champs.

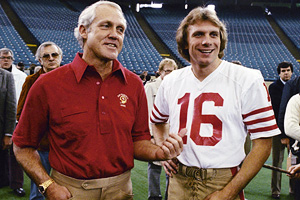

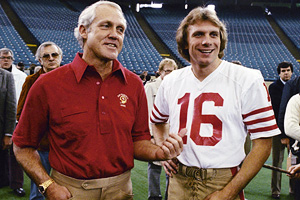

AP Photo/Atkins

Bill Walsh, Joe Montana and the 49ers earned an all-expenses paid trip to suburban Detroit to culminate the miracle 1981 season.

Smart moves they made: The 49ers made Joe Montana the full-time starting quarterback, and he earned the first of eight career Pro Bowl selections. Acquired veteran defensive stalwarts Jack "Hacksaw" Reynolds and Fred Dean. Drafted three starting defensive backs: cornerback Ronnie Lott, No. 8 overall; cornerback Eric Wright, second round; and safety Carlton Williamson, third round.

Where they got lucky: The Niners went from No. 27 in the NFL in total defense in 1980 to No. 2 in '81. They also improved in turnover differential from No. 20 to No. 1. Montana and Dwight Clark teamed up to complete one of the most famous passes in NFL history, "The Catch," to seal the NFC championship.

Was it a fluke? Yes and no. Sure, San Francisco went on to capture four more Super Bowl titles through the 1994 season, and the team missed the playoffs just twice from 1981 to '98, winning 10 or more games in a season 17 times during that span. But let's not be so quick to forget the Niners flopped to 3-6 during the strike-shortened 1982 season. So much for consistency.

Miracle rating:

1977 Portland Trail Blazers

1975-76: 37-45, team had never finished above .500 or made playoffs in six previous NBA seasons.

1976-77: 49-33, second place in Pacific Division with No. 3 seed in Western Conference, won NBA title.

Smart moves they made: Acquired Maurice Lucas in the ABA dispersal draft. Lucas led the Blazers in scoring, offensive boards and minutes played. Also signed another ABA evacuee, Dave "Pinball" Twardzik, who led the team in field-goal percentage. Hired Jack Ramsay as head coach. Allowed Bill Walton to cultivate the look later adopted by Charlie Steiner in the "Follow me to freedom" "SportsCenter" ad.

Where they got lucky: Walton enjoyed a relatively healthy year, logging the most minutes of his career. He also led the league with 14.4 rebounds and 3.2 blocks per game. Portland went 5-12 in the 17 games Walton missed.

Was it a fluke? Yes and no. Walton played only one more season for the Blazers, and the team retooled. Portland missed the playoffs just once from 1976-77 through 2002-03, but it didn't reach the NBA Finals again until 1990 with a completely new roster.

Miracle rating:

1969 New York Mets

1968: 73-89, ninth in the National League, but easily the best season in the franchise's seven-year history. In the year of the pitcher, Mets hit just .228 (last) with a .277 OBP (last) and .315 slugging percentage (last). However, they did rank second in fewest runs allowed.

1969: 100-62, rallied from 10 games back of the Cubs on Aug. 13 to win NL East (they had win streaks of 10 and nine games in September) and beat the Braves in the NLCS and upset the Orioles in five games in the World Series.

Smart moves they made: Collecting young power arms. Tom Seaver, who would go 25-7 and win the Cy Young Award, and Jerry Koosman, were already in place. Rookie Gary Gentry joined the rotation and went 13-12. Tug McGraw, after spending 1968 in the minors, had a big year in relief and was joined by another young reliever named Nolan Ryan. Otherwise, the Mets stayed with their 1968 lineup, replacing only veteran third baseman Ed Charles with rookie Wayne Garrett (who was awful). The team's only in-season move was to acquire first baseman Donn Clendenon, who hit 12 homers in 202 at-bats.

Where they got lucky: The offense improved just enough (ninth in runs out of 12 teams), thanks to big years from outfielders Cleon Jones (.340) and Tommie Agee (.271, 26 home runs, after .217 in 1968) and fourth outfielder Art Shamsky (.300, 14 HRs in part-time duty). Based on their runs scored and allowed, the Mets overachieved by nine wins.

Was it a fluke? Essentially, yes. They led the NL in fewest runs allowed the next two seasons as Seaver remained great. But Koosman was never as good again as in '69 (17-9, 2.28). The Mets were never able to overcome poor offenses and won 83, 83, 83 and 82 games the next four years. Hey, at least they were consistent. They did reach the World Series in 1973 despite winning just 82 games but lost in seven games. Some bad trades (Ryan, Amos Otis) didn't help.

Miracle rating:

1967 Boston Red Sox

1966: 72-90, ninth in the AL -- their eighth consecutive losing season. Finished eighth in AL in attendance (Boston wasn't always so fanatical about its baseball).

1967: 92-70, won pennant on final day, the franchise's first since 1946, thanks in large part to Carl Yastrzemski's memorable September: .417/.504/.760, nine home runs and 26 RBI. Lost the World Series in seven games to St. Louis, but the season became known as the "Impossible Dream."

Smart moves they made: The Sox made no major offseason moves, but did insert rookies Reggie Smith in center field and Mike Andrews at second base, joining second-year starters George Scott and Joe Foy. With Rico Petrocelli (24) and Tony Conigliaro (22) also starting, Yaz was the old man at 27. The team acquired veteran starter Gary Bell during the season and he became the club's No. 2 starter, going 12-8, 3.16.

Where they got lucky: MVP Yastrzemski had a career year, winning the Triple Crown while slugging nearly 200 points higher than '66. The Sox got good work out of journeyman pitchers Lee Stange, John Wyatt and Jose Santiago. Third-year starter Jim Lonborg emerged as an ace after going 19-27 his first two seasons. He went 22-9 and won the AL Cy Young Award.

Was it a fluke? No. Even though Lonborg would tear up his knee that winter in a skiing accident and Conigliaro would never fully recover from a near-fatal beaning in August 1967, the Sox would not have another losing season until 1983 (although they captured just one division title in that span). This was also the season that turned Boston into a baseball-crazy city as it led the AL in attendance in '67 and ranked first or second the next 11 seasons.

Miracle rating:

1914 Boston Braves

1913: The sad-sack franchise of the NL, the Braves finished 69-82, fifth in the NL, their 11th consecutive losing season. That was actually a good year; they had lost 100-plus games the four previous years.

1914: The Braves were in last place as late as July 18, with a record of 35-43. They went 59-16 the rest of the way to finish 94-59, capturing the pennant by 10½ games. They then swept the heavily favored Philadelphia A's in the World Series, earning the moniker the Miracle Braves.

Smart moves they made: Perhaps the key move was hiring manager George Stallings in 1913; he became the first manager to platoon extensively throughout his lineup. In a big trade before the season, the Braves traded second baseman Bill Sweeney and cash to the Cubs for second baseman Johnny Evers. Sweeney was a decent player but on the decline (he would hit just .218 for the Cubs) while Evers, four years older, would win the Chalmers Award as NL MVP (as much for his fiery energy as on-field statistics).

Where they got lucky: First baseman Hap Myers and catcher Bill Rariden jumped to the new, rival Federal League, but their replacements, Butch Schmidt and Hank Gowdy, actually proved to be upgrades. The Braves also took advantage of a downswing in the NL -- the Cubs, Pirates and Giants had dominated for years, but the NL would see four different pennant winners from 1913 to 1916.

Was it a fluke? Essentially, yes. Stallings rode second-year starter Bill James ("Seattle Bill") as hard as he could -- James pitched 332 innings (third in the NL) and ranked second with 26 wins and a 1.90 ERA. He won games in the World Series but when he showed up the next year with a dead arm, the Braves were done (he would win only five more big league games). Evers was also never a full-time player again. The Braves stayed above .500 two more years before falling into another long losing spell (below .500 in 13 of the next 14 seasons).

Miracle rating:

Original here

Original here